Simplicity on the Far Side of Complexity

Recently, I posted some thoughtful questions about how we read the Book of Mormon. Specifically, I posted questions about why we feel drawn to labeling Nephites as good guys and Lamanites as bad guys, and I asked questions about what negative ramifications that incorrect simplification might have. I asked for advice about how to answer my kids’ questions about “Who were the good guys?” in the Book of Mormon.

I received a lot of great comments, but one comment felt somewhat dismissive to me. It was from my favorite seminary teacher from my youth. Instead of engaging with the questions, the comment said “Keep it simple—keep the commandments, in this there is safety and peace.” It caught me off guard and caused me some soul searching. I am a huge fan of simplicity. I feel in my heart that I highly value keeping things simple. But, it was obvious that I was coming across to a trusted teacher of mine as over-complicating things.

I definitely took her point to heart and tried to evaluate if I had unnecessarily convoluted things in any way. At the same time, this soul-searching caused me to further evaluate if simplicity and complexity are always enemies and opposites or if maybe there is some interplay. I think we can all agree that simplicity is a worthy goal, but can it be accomplished without wading through complexity?

Pondering this question led me back to a quote I heard Bruce C. Hafen share. He’s quoting American judge Oliver Wendell Holmes who says,

I would not give a fig for the simplicity [on] this side of complexity. But I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.

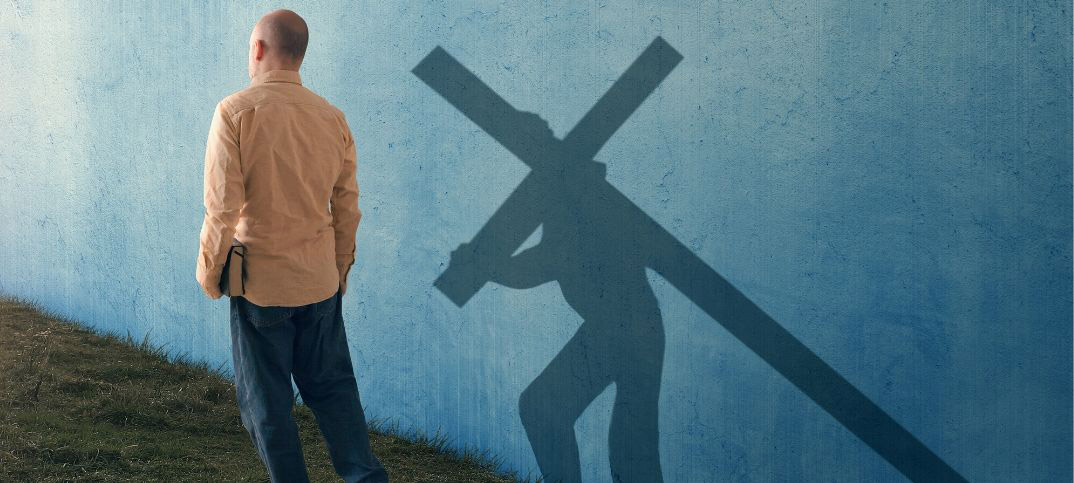

This introduces the idea of two very different kinds of simplicity: one that is naïve and has never passed through complexity, and the other is a simplicity that has been achieved after traversing through complexity. This quote gives the feeling that maybe these two types of simplicity are so inherently different that maybe it’s a misnomer to call them by the same name. Either way, I wanted to explore the difference between the two and their interplay with complexity.

I started out trying to think of any scriptures that might be helpful in how we think about simplicity, complexity, and simplicity on the other sides of complexity. I thought of the allegory of the seed and how, for simplicity’s sake, one may fail to put the seed into the ground. It can be complicated to try to get it to grow. Putting the seed in the ground could ruin and waste the seed. You could lose it. But, it also can never grow into anything if you don’t put the seed into the dark wet ground and let it die so that something beautiful and useful can grow.

That connection was kind of helpful, but I felt like I could find an even better fit. I thought a lot about Jesus’s invitation in Matthew 18:3 where He says,

I say unto you, Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.

In my mind, I kept thinking the verse said “except ye return and become as little children.” That felt significant in this current conversation, because the scripture doesn’t say to stay as little children — to never grow up and gain experience. But it says to “be converted, and become as little children.” Many versions replace “except ye be converted” with “except ye change” and “except ye turn.”

I thought I must have just remembered the verse incorrectly until I looked it up in the Spanish bible where it uses the word “volver,” or “to return.” This drove home the idea for me that this verse isn’t saying there’s something important about staying as a child, but something altogether different about what it means to “return” to being like a child after you’ve gained experience and waded through complexity. If you can gain experience and gain knowledge, and then from there return to the innocence and simplicity of a child, then maybe that’s a huge step to becoming like God.

The popular verse in 1 Corinthians 13:11 then came to my mind. Let’s see how it correlates:

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

This verse could easily be seen as contradicting Matthew 18:3 if there was just one way of being like a child (i.e. “simplicity” for our purposes). Stitching the concepts together we understand that there is something vital to our progress about growing up and leaving behind childish things. Once we’ve gained that experience, returning to become as a little child has new meaning. It’s actually a completely different state, but it combines the wisdom of experience with the innocence of a child.

In other words, it is simplicity on the far side of complexity.

Finding those verses was very satisfying as far as creating a doctrinal background for the concept of two inherently different kinds of simplicity and their interplay with complexity, but I still wanted to think of a way to maybe illustrate it better — to really paint the picture. One of the most visually engaging stories from the Book of Mormon came to mind: Lehi’s vision of the Tree of Life.

Imagine that you’re part way through your journey to the Tree of Life. You’ve been hanging on to the iron rod like you were always told, and you’re holding onto hope that it really leads to the worthwhile reward of the fruit and tree; however, presently, you are realizing that you were not quite prepared for these mists of darkness. You haven’t actually seen the tree or felt the warmth of its light for days, maybe years. The iron rod is cold and holding on is starting to literally hurt. You’ve recently had loved ones–friends and family–step away from the rod and you miss them. You can’t help but wonder what you and others could have done to better help them stay. You wonder aloud to your fellow travelers why no one warned you about all these things. They were made mention of, but you do start to feel frustrated that a lot of the talk was all about how amazing of a journey it was and all you had to do was just “hold to the rod.” You start to think of ways you might better help others behind you prepare for what’s ahead.

While you still can’t see the tree, somehow you can still see the large and spacious building. You’ve built up a lot of resistance to their mocking, but the frustration you’re feeling about not being told how hard this would be has made it more difficult to ignore their jeers. In the midst of all of this, suddenly you hear another voice. At first you think it’s another jeering voice from the large and spacious building, but then it sounds somewhat different. You realize it’s coming from someone far behind you, someone who is up on a hill back at the beginning of the rod. Someone who hasn’t commenced the path yet. This is what you hear:

“What’s going on? Why are you hesitating? You’re obviously slowing down. You’re focusing on the wrong things! Look, this is simple, you hold to the rod until you get to the tree. I can see it all from here. Don’t complicate it! Just hold to the rod and get to the tree.”

You answer back: “Of course, that’s all good and well, but have you ever gotten to this part of the path? Have you ever been to the tree? There’s a lot you’re leaving out!”

“See? You’re distracted. I told you, it’s simple! Just hold to the rod and get to the tree. I can see it perfectly from here. Why are you complicating it?” they respond.

Can you imagine how frustrating that would feel? You are holding onto the rod, and you do want to get to the tree. You know the iron rod is the way to go! But, it doesn’t feel good to be told by someone who’s not even on the path and hasn’t even been to the tree that you’re over-complicating things just because you’re acknowledging that it’s harder and more complicated than you expected. You are actually on the path, and you are actually thinking of how you can make the journey better for others.

Yes, what the other guy is saying is technically true, but you’re not after the view he has–from the start looking forward–you’re after the view from the tree, from the end looking backwards. Both views will equally reveal the overall simplicity of the adventure. But only one allows you to become something and allows you to reside in the presence of God where the complex things you passed through will finally feel simple in the light of the joy and peace you have achieved.

This is a principle similar to the concept that we can’t know the good without the evil. We can’t know true simplicity without traversing complexity. Simplicity is the goal! We have to remember that, otherwise we may easily get lost in the complexity. But it is the simplicity on the far, and sometimes very far, side of complexity that is the simple peace we all yearn for.

“One of the great challenges in this world is knowing enough about a subject to think you’re right, but not enough about the subject to know you’re wrong.” ― Neil deGrasse Tyson