Finding Peace in Divine Clouds

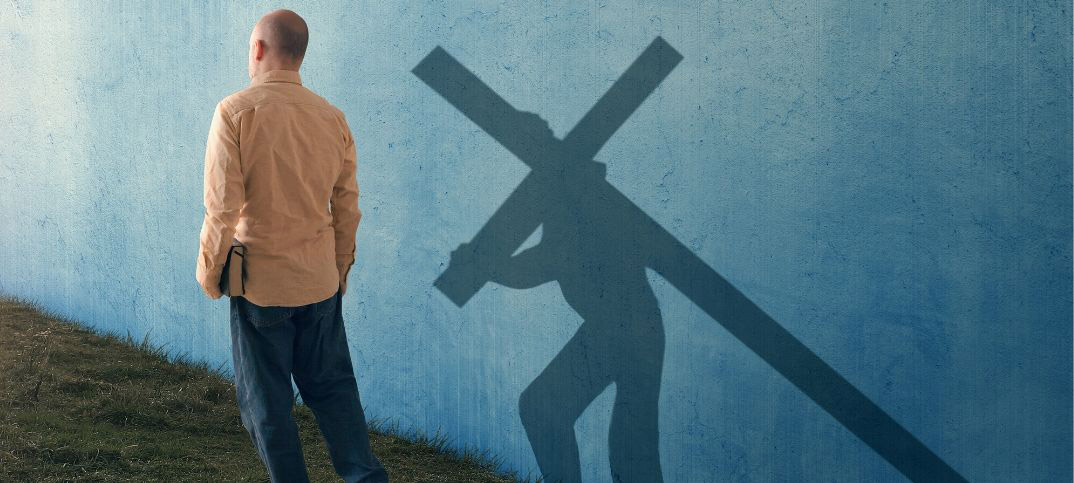

Over the last several years I have undergone many transitions, evolutions, and transformations in my discipleship and relationship with God. Joseph Smith once famously stated that,

I am like a huge, rough stone rolling down from a high mountain; and the only polishing I get is when some corner gets rubbed off by coming in contact with something else, striking with accelerated force against religious bigotry, … Thus I will become a smooth and polished shaft in the quiver of the Almighty (TPJS, p. 304).

While I have certainly not run into religious bigotry and suffered the torment of mobs and violence that Joseph Smith (and the early Saints) endured, in my own small way I feel what many of us feel as rough stones that are tumbling through life — seemingly out of control — and being chipped away here and there by the sudden and blunt forces of life. Maybe one day I, too, will be a “polished shaft in the quiver of the Almighty.”

In many of these “blunt” times over the last several years I have had to wonder where God was in and through it all. I have had many “blunt” conversations with God. We have had a few reckonings, and I have had some pretty strong things to say to Him about Him. “Pretty strong” may be a bit of an understatement. At times I’ve shouted and railed at Him (both proverbally and literally), and at times I’ve dropped to my knees in near hopelessness feeling completely at the end of my rope. What kind of supposedly “loving” God is this that I say I believe in and worship? The names that I’ve had for who and what that kind of “God” must be to be so aloof while I am in despair are not suitable and appropriate to list here.

Over and over, however, I found that God’s love was bigger than my hurt. God’s grace was greater than my pain. God’s compassion went far beyond my name calling, my yelling, and my anger. I deserved nothing of the goodness that I received from Him. I still don’t fully understand it but for the first time in my life I glimpsed the goodness and love of God while actually in my pain and suffering, and that moment changed my life. I don’t even know how to explain that experience to anyone else, but all I know is that it happened to me and that I experienced it.

Who is this God that I worship? What kind of God is it that I believe in? How would He let me (and everyone else) experience destitution and despair and still be considered “loving”?

And yet, in my hurt, I still felt something inside of me pulling me deeper into a relationship with this entity that I call “God” that confused me, seemed entirely inconsistent, and allowed my sorrow to continue.

Through all of that, and even still, I experienced a God that sat there with me and experienced all of that with me. To borrow a phrase from Joseph Smith, I knew it, and I knew that God knew it. In moments of desperation I often told God, “This moment really, really sucks… this hurts…” In a few very precious moments I felt Him saying back, “Yeah, I know… This does suck… But I’m right here going through it with you.” I was angry, but in those moments I learned that I was not alone. Somehow that was enough.

I also know I am not alone in my story. As I’ve talked with friends and family over the years, I’ve learned that it seems as though most (if not all) of us go through these similar moments in our own ways. Over the last year especially I’ve seen an incredible amount of pain and anguish, and I’ve seen many questioning the goodness and love of God through it all.

As I was reading through the Book of Mormon last year, a story in Ether stood out to me in a completely new way. The story of the Jaredite exodus into the promised land seemed to be an allegory of my own life. Of all my questions I was having about God and His nature, I found those questions illustrated in the symbolism of God-as-a-cloud leading His people through a desolate wilderness toward a promised land.

In both the Biblical Israelite Exodus story and in the Book of Mormon’s Jaredite Exodus story, God appears to the people as a cloud that leads them into an unknown wilderness towards a prepared land of promise (Ex 13:21; Ether 2:5). While there is great value in treating this story as actual history, there is also a rich and often overlooked meaning to be found in its allegorical telling as well.

The story in Genesis begins when “the earth was without form and void.” It was then that “the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters” (Gen 1:2). In scripture, water is commonly symbolic of chaos, disorder, entropy, death, destruction, or oblivion. Oftentimes water can also signify something that is undefined or not yet fully understood, such as in a cloud or mist/vapor. Water and cloud can be symbolic veils where behind or through the water/cloud is entrance into an unknown mystery.

The Dictionary of Biblical Imagery helps us to understand the symbolic nature of water (as in the creation account in Genesis):

God’s continuing providential oversight of his world is presented in terms of the mastery of water by the divine word. The original creation has the creatures called into existence by divine fiat or utterance. This created order is preserved as God maintains the sea within bounds and so, by implication, restrains the background threat of chaos…

Noah’s flood at several points reflects the ancient understanding of the cosmic waters. The flood is the return of the waters of chaos, which the creation in a sense undone, making way for the new creation… (pg 929; italics added for emphasis)

The same book defines the symbolism of a cloud as

God’s presence but also his hiddenness. No one can see God and live, so the cloud shields people from actually seeing the form of God. It reveals God but also preserves the mystery that surrounds him. (pg 157; italics added for emphasis)

And, finally, the same dictionary defines the symbolic value of mist:

Mist occurs rarely at sea level in Palestine (though regularly on mountains [as clouds]), perhaps accounting for the sparsity of [its] reference [in the Bible]… In the book of Job, Elihu’s preview of the voice from the whirlwind cites the mist that God distills in rain as an example of God’s transcendent and mysterious power of nature (Job 36:27).

To the poetic imagination, mist or vapor is above all an emblem of transitoriness and insubstantiality, based on its tendency to dissipate quickly in the heat of the morning. (pg. 562; italics added for emphasis)

The commonality here between the various symbols of water, cloud, and mist/vapor is that they are all basic forms of something in perceived disorder (i.e., chaos) or something that is yet undefined or unknown. Water, cloud, and mist do not hold their own shape, and they are mostly perceived by the conditions of the environment around them. Water, cloud, and mist pour over and cover everything, but our experience is that they carry no real form of their own. Water, cloud, and mist cannot be formed or molded by human hands.

As both the Israelites and the Jaredites each pressed on into their own wilderness (symbolic of our own lives and journeys in following “God” into the unknown), the symbolism of a cloud is to represent that they did not yet fully understand what it is that they were following. God, in their limited view, was an undefined cloud that they followed into a land and into an experience with the divine that they had never known before.

Even though they did not yet fully understand, they pressed forward step-by-step into following this undefined and uncontainable cloud into the unknown. As Jesus would later tell the woman at the well, “Ye worship ye know not what” (John 4:22), so the Israelites and the Jaredites followed in faith a God they did not yet fully understand. However, with each step, God provided for their needs and kept revealing Himself as much as they would accept to know Him. The journey was still long and painful (often made longer by their own choices), but the cloud was ever present in guiding them.

The Israelites, at one point, sought to define God by their own parameters and meaning, as the famous “Golden Calf” was constructed while Moses was speaking with God on Mount Sinai. This idol was not merely a false Egyptian god that the Israelites knew from their time in Egyptian captivity, but it was meant to be the representative embodiment of Yahweh (Jehovah). A God of cloud could not be molded into such a shape by human hands. It seems that the Israelites sought to make a god in an image that they could comprehend (the anti-cloud as it were), that they could model, that they could see, and that they could make sense of.

It also seems that God knew that this was going to happen.

When Moses was first called by the Lord, Moses inquired to know His name. Moses knew that the God he was speaking to was not of the gods of Egypt. We can perhaps sense a little trepidation in Moses as he seeks to go forward into Egypt with the full power, might, knowledge, and understanding of His own God in order to rally the Israelite slaves and battle the massive Egyptian system. Moses inquired, “Behold, when I am come unto the children of Israel, and shall say unto them, The God of your fathers hath sent me unto you; and they shall say to me, What is his name? What shall I say unto them?” (Ex. 3:13).

God does not give Moses that full understanding. Instead, he responds “I AM THAT I AM: and he said, Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, I AM hath sent me unto you” (Ex. 3:14).

In other translations of this text from both Jewish and Christian traditions, many scholars have interpreted this name of God in many variations from “I am who I am” and “I am he who is,” to “I am because I am” and “I will be with you.” The general sense here is clear that God is not going to reveal Himself to Moses, the Israelites, or the Egyptians in a mere name or propositional truth statement. God will reveal Himself through experience as His children seek to enter into the mystery of who and what He is. I AM revealed Himself to those who would follow a cloud — a seemingly undefined, unknowable mist — and would lead, guide, and show by experience that He would deliver them in every needful thing.

In both of these stories — of the Israelites and of the Jaredites — God does reveal Himself more and more clearly and thoroughly, and Moses and the brother of Jared both see God face to face (Exo 33:11; Ether 3:13). What started as a journey of discipleship in following an undefinable cloud (something illusive and seemingly without order) eventually became known face to face with a witness of the embodied Christ.

When the Pharisees came to Jesus declaring themselves as “Abraham’s seed,” they, like the ancient Israelites, had made a doctrinal golden calf in their own image and likeness. They imagined God existed in a certain way and they refused to see God in any other way. Their immovable and unchangeable idea of God was their idol. They refused to humble themselves and repent (i.e., to choose to see God, themselves, and each other in a new and fresh view).

The Pharisees wanted to find a way to legally kill Jesus, and Jesus knew it. Their questions were not honest or sincere, but they sought to lay careful ploys to ensnare him in legal traps. They couldn’t see beyond the eyes of their false selves, and Jesus, seeing their wilful and prideful ignorance, knew that he could not reach them alone by arguing in propositional truth claims and legalisms.

Jesus responded to the Pharisees, “Your father Abraham rejoiced to see my day: and he saw it and was glad,” and the Pharisees mockingly responded, “Thou art not yet fifty years old, and hast thou seen Abraham?” To this, Jesus, in following the same pattern that He had with the ancients announces, “Verily, verily, I say unto you, Before Abraham, I am” (John 8:56-58). The true and embodied Messiah was directly in front of them, and yet the Pharisee’s pride blinded them and they could not even perceive, let alone follow, the symbolic God of cloud and mist. They were too busy worshipping their own ideological golden calf.

As I read through and studied about God as a cloud, I realized in my own way that I was entering the same pattern of being with God that the children of God have done throughout all time. I couldn’t see or understand the mystery of the God that I was being drawn into. I was literally following a symbolic cloud. I’m still following divine clouds. I suspect in many ways I always will.

Yet, like Moses and the brother of Jared, in my own way, I have seen the face of God when I, while in my pain and suffering, was offered a glimpse into the universal and unending love of God. Before, I would wish that I could say, like Alma the younger, that when I caught hold of the atoning goodness and love of God that “I could remember my pains no more” (Alma 36:19), but in that moment I learned perhaps a different lesson. I learned to begin to see the cloud-like God leading me into a promised land. That does not necessarily make the pain of the journey any less real, but I have learned by my own experience that God’s love is present in my own suffering.

Have you ever felt drawn into the mystery of God? Asked differently, have you ever been led by God without really knowing where you were going or what you were doing? Have you felt that internal ‘pull’ to follow an impression, feeling, sense, or inspiration into your own ‘wildernesses’ when you didn’t even yet fully know that it was absolutely coming from God? When have you followed that ‘cloud’ in your own way and into your own personal wilderness? Have you thought of God in one way and then through His loving persistence discovered Him to be another way? How has God slowly revealed more and more of Himself to you as you ventured into the dark?

Sometimes we feel a sense of security in making for ourselves a god that reflects our own imperfections. We feel a sense of comfort in the known. To venture into the unknown can be scary. However, hope is born in the journey. As we follow I AM into the wilderness of our lives, we begin to see that He continues to reveal Himself more and more until we have a more perfect knowledge of the God whom we follow and worship.