The Healing Power of Good Friday

The Friday before Easter Sunday, traditionally known as Good Friday, marks the crucifixion of Jesus. As Latter-day Saints, we don’t usually pay much attention to this day, and perhaps when we see it printed on the calendar we wonder what is so ‘good’ about it. With a cultural aversion to the symbol of the cross, we tend only to join other Christians in the world with observing the Resurrection on Easter Sunday; accepting the Savior’s death as a necessary part of the process of atonement, but the living Christ is the true miracle we point to. After all, it is the arrival of the living Christ we look forward to receiving in Zion.

But there’s a problem. We have consistently failed to establish Zion in this dispensation. We have yet to successfully build up a society where all people are “… of one heart and of one mind, and dwel[l] in righteousness [with] no poor among [us].” Of course, we can point toward several outward reasons for this failure- the largest being the forceful abandonment of the designated gathering place in Missouri in 1838 and the violence and strife (on both sides) that lead up to it. In today’s church, we can also point to the smaller-scale strife between members as we judge, quarrel, and contend with each other.

Fortunately, the struggles we have in establishing Zion in the restored church are the same as those experienced in the primitive church. We need only look to the prophets of that dispensation to diagnose the problem in ours; specifically we can look to the writings of James, one of the three “pillars of the church” (Galatians 2:9) in the first century, and the brother of Jesus himself. We as Latter-day Saints love James’ epistle for the role it plays in the Joseph Smith narrative, but unfortunately we usually only read the first five verses, which is unfortunate because it’s full of wisdom for the Saints in our day. In fact, it was written as a “wisdom book’- a re-tooling of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount in the form and tradition of the Old Testament book of Proverbs. In chapter 4, verses 1-5, James speaks to the members of the church who were failing to live as a Zion people just as we are today:

From whence come wars and fightings among you? come they not hence, even of your lusts that war in your members?

Ye lust, and have not: ye kill, and desire to have, and cannot obtain: ye fight and war, yet ye have not, because ye ask not.

Ye ask, and receive not, because ye ask amiss, that ye may consume it upon your lusts.

Ye adulterers and adulteresses, know ye not that the friendship of the world is enmity with God? whosoever therefore will be a friend of the world is the enemy of God.

Do ye think that the scripture saith in vain, The spirit that dwelleth in us lusteth to envy?

There is a lot to unpack there, but right at the very beginning, James diagnoses the problem as “your lusts that war in your members.”

In modern English, we think of “members” as “members of an organization” (like a church). It’s easy to interpret it that way. But “members” at the personal level also refers to the specific parts within an individual. So what James is telling these early saints- and us- is that their outward arguments and wars were a direct result of the inward wars that they were having with themselves. They were giving into their lusts of various kinds and they were giving into envy. They were living from their own internal, psychological wounds and then projecting out into the world- and into the church. Just as James diagnosed the problem in his day, he diagnosed the problem in our day.

Why don’t we have Zion? Why aren’t we united? Because we as individuals inside are fractured. We are warring with ourselves over our lusts and envies, and we’re projecting that out to everyone else. At the individual, internal level, we are not of one mind, of one heart, dwelling in righteousness with no poor among us. Modern psychology has increasingly shown that each of us is made up of several sub-personalities and that much of our distress comes when these personalities are not united- some parts of us, wounded by trauma, are shunned entirely from the system. So long as our parts- our members- are warring within us and some are excluded, we have “poor among us.” Trying to build a Zion community with such fractured individuals would be–and has proven to be–as fruitless as building a solid temple with cracked stones.

These concepts are deeply personal for me. I have dedicated the last several years of my life to the task that the great psychologist Carl Jung called ‘individuation’–or becoming one, whole individual by discovering, healing, and integrating these fractured parts of myself. As Jesus revealed, if we are not one, we are not His (D&C 38:27). I began a daily spiritual discipline of exploring my subconscious attitudes through writing exercises, with the intent of discovering my inner wars and contentions and from there being honest with myself about how I project these things onto the people around me. As James wrote, these outer problems have an inner source. This has turned out to be difficult, unflattering work, but it has certainly been worth it. Through this daily discipline and commitment to honesty, I have received waterfalls of personal revelation, all teaching me the importance of learning to surrender.

For example, one day all of this work had stirred up memories of several serious offenses against me that had been committed by a particular person. As I thought about these experiences, I understandably grew angry. I was furious, but as I sat there fuming about the past, the familiar still, small voice of the Holy Spirit spoke to me: “surrender.” I didn’t find this very helpful and I grew angrier. I began to wrestle with God in very raw, emotional prayer. What I expressed to my Heavenly Father in that moment was that I didn’t want to forgive. If I forgave, it would be over. I would be left unsatisfied because justice had not been done. The Lord replied firmly but lovingly “You are not the arbiter of justice. I am, and if I can forgive, then so can you.”

This of course was an emotional moment. I knew the wrestle had been won. I thought maybe I could forgive, but I didn’t know how to forgive.

As I continued to prayerfully search for answers, I found a strange but helpful teaching in the Book of Mormon; Jacob 1:7-8. Here, the prophet Nephi is old and is preparing to die, and Jacob, his younger brother, is taking up his prophetic mantle:

Wherefore we labored diligently among our people, that we might persuade them to come unto Christ, and partake of the goodness of God, that they might enter into his rest, lest by any means he should swear in his wrath they should not enter in, as in the provocation in the days of temptation while the children of Israel were in the wilderness.

Here we have a theme of exile. Jacob is comparing the budding new Nephite nation to their Israelite ancestors. In a story we know well and review this time of year, the Israelites were brought out of Egypt but were stopped in a holding pattern in the desert because they weren’t prepared to enter into the promised land and the rest of the Lord.

Wherefore, we would to God that we could persuade all men not to rebel against God, to provoke him to anger, but that all men would believe in Christ, and view his death, and suffer his cross and bear the shame of the world; wherefore, I, Jacob, take it upon me to fulfill the commandment of my brother Nephi. (emphasis added)

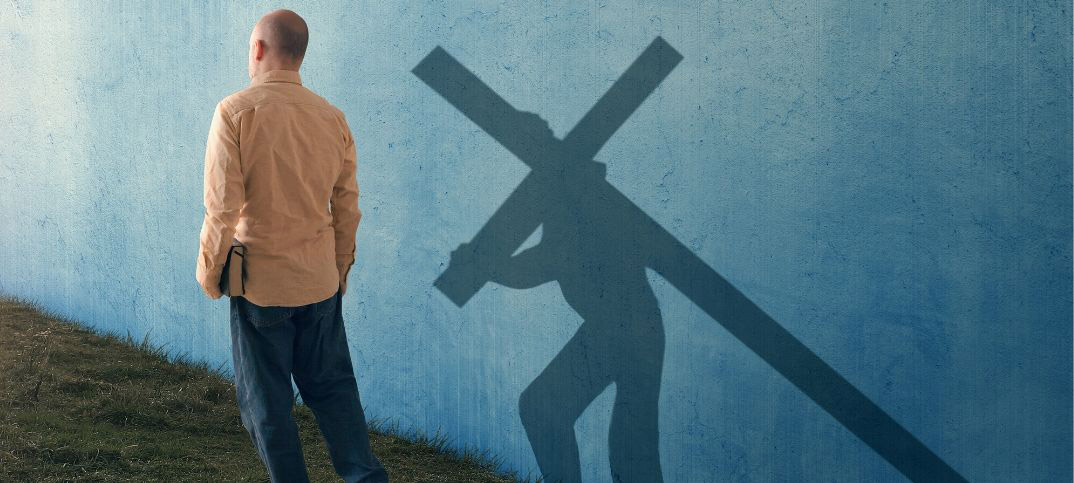

This is a strange thing to find in the Book of Mormon. We as Latter-day Saints don’t like crosses, and we don’t like to “view His death.” We like Easter a lot more than Good Friday, but Jacob invites us to do what we don’t like to do, and to look upon something we’d rather not see.

The Savior, we always say (even rotely), died for our sins. When the question is asked in our church classes, the answer that will always satisfy the asker is something like “the Atonement satisfied the demands of justice,” and that’s certainly true- there are plenty of scriptures that will back up that answer. Through this experience of revelation and surrender and forgiveness, however, I came to see things differently.

We tend to talk about the suffering of Jesus as if it satisfied some mysterious universal law of “justice” out in the aether that even God is beholden to- and that may be. I don’t understand or even know the metaphysics of the universe and the gospel. What I have come to understand, however, is that leaving the answer there, in the abstract, is too safe to be useful. It’s not transformative.

The hard lesson that I came to learn is that the sense of justice that Jesus came to satisfy is mine. The real, transformative question in my relationship with the Atonement is simply this: does Jesus satisfy my demand for justice?

The lesson seems to be this: when we think about people that we don’t want to forgive because they have harmed us, and when we think “Justice won’t be served if I just forgive them… Someone needs to suffer for this, because it made me suffer!” That’s when Jesus steps in and says, “I did. Let my suffering satisfy you. Let my death be enough.”

Do we view His death? If we vividly imagined the death of Jesus, as horrific as it truly was; if we truly saw the suffering of Jesus in the Garden and His painful, humiliating death and torture on the cross; and if we did so sufficiently, we would be horrified by our own calls for justice. We would see that our demands were fulfilled and we wouldn’t like what we saw. We would find ourselves quite compelled to stop demanding justice if we truly saw the perfect, beautiful Son of God suffering all the demands of justice. If we viewed His death properly, it would satisfy us. The war and envy and lust inside ourselves would stop, because we would come to see ourselves as He sees us- as we truly are. Then, the wars outside would stop, because we would stop projecting all this inner turmoil onto all the other people around us. We would come to experience this inner Zion that is satisfied by the death of Jesus, and from there we could begin to build the outer Zion. We could then bring about the Second Coming of Jesus- in more ways than one.

While this may be a new way to understand these teachings, none of this is arcane. It’s the very meaning behind the ordinances of the Gospel. These ritual experiences are specifically given to us as aids in representing, remembering, and viewing the death of Jesus. For example, the apostle Paul teaches us that baptism represents the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus (Romans 6:3-4). To ‘represent’ something literally means to ‘re-present’ it- to make an event of the past present again. By baptism, we make the death of Jesus present again so we can view it- and even participate in it ourselves. The Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper we gather to partake of each week operates on a similar principle; If you look at the sacrament table, it looks like a casket with a burial shroud on top of it. Sacrament meeting is a ritual funeral where we gather to re-present the death of Jesus Christ, to attend His funeral, and await His resurrection. In fact, the ordinance is an invitation to symbolically bring about that resurrection every week.

When the priests administer the sacrament, first they break the bread, which symbolically dismembers the body of Christ. Then, rather strangely, one of them kneels down and asks God to help us in the congregation to re-member the Christ that he just dis-membered. Remembering Jesus, as we are invited to in the sacrament prayers, is so much more than conjuring up mental images of Him throughout the week. To re-member literally means to put broken parts back together. For a people that claims to be focused more on the living, resurrected Jesus, it’s interesting that we often forget the second half of the ordinance- the re-membering. As the broken pieces representing Jesus’ body are passed out into the congregation and consumed, the task is then to become the body of Christ by bringing the pieces back together into one, living whole- first within ourselves, and then in community. This is a Second Coming. This is Zion.

I’ll finish with a final thought from the Book of Mormon, borrowed from brother Thomas B. Griffith’s excellent devotional, The Very Root of Christian Doctrine:

The climactic event in the Book of Mormon is the visitation of the resurrected Jesus to the people of the Americas, which begins in 3rd Nephi, chapter 11. In this chapter, the people have gathered at the temple after a serious natural disaster has collapsed their already decaying civilization. Suddenly, they hear a voice from heaven and look up to see a man descending down onto the steps of the temple. Upon seeing this, all the people fall down and worship Him, because of the prophecies that had been given. Jesus then invites them- one by one- to feel the nail marks in His hands and spear mark in His side- the physical evidence of His horrific death. After this, they fall down again, but this time they shout,

Hosanna! Blessed be the name of the most high God!

The narrator then tells us:

And they did fall down at the feet of Jesus and did worship him. (verse 17)

As brother Griffith points out, there seems to be a big difference in this group’s worship before and after they inspect Jesus’ scars. The first time, they were silent, but after having a personal, visceral experiencing seeing and touching these emblems- in effect, viewing His death- they suddenly had a renewed sense of who they were dealing with. This time, they shouted “Hosanna!” a Hebrew appeal meaning “save us now!”

After this visitation, it is these people- the Nephite remnant- who go on to build one of the few Zion communities we have record of, for four whole generations; and we know what made these people different. They had viewed the death of Jesus through physical, personal, visceral contact with the emblems of His suffering. This ultimately healed them- they were satisfied. They had surrendered.

This is the invitation extended to all of us by Good Friday.